An industrial chemical has infiltrated the drinking water at a trailer park near Shaw Air Force Base in Sumter County, worrying residents, angering elected leaders and forcing state health officials to respond.

Lab testing paid for by The Post and Courier shows tap water at the Crescent Mobile Home Park, a small community located directly next to the military base, contains significant levels of a chemical known as perfluorooctane sulfonate.

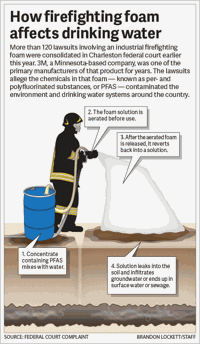

The man-made compound — commonly referred to as PFOS — has been used by the military since the 1970s as part of a firefighting foam that service members routinely sprayed during accidents and training exercises.

Last year, an environmental study by the Air Force found large concentrations of the same chemical in the groundwater under six locations at Shaw, one of South Carolina’s largest military bases.

That study noted how Crescent pulled its drinking water less than a mile from some of the highly contaminated groundwater. It also suggested the chemicals could have already spread off the base.

Despite those warnings, neither state nor federal officials immediately moved to determine if the water at Crescent or other neighboring communities was tainted with the chemical.

That’s why The Post and Courier conducted the testing itself.

The newspaper obtained a water sample from the trailer park late last year, and hired researchers at the University of Rhode Island to test it for PFOS and a number of related chemicals known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances — PFAS for short.

The lab results are a first in South Carolina: They show the drinking water at Crescent contains PFOS levels above an advised health limit set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The EPA's recommended limit is 70 parts per trillion. But the water sample from the trailer park contained chemical concentrations of 96 parts per trillion.

Jitka Becanova is one of the researchers at the University of Rhode Island’s STEEP program, which specializes in sampling for PFAS chemicals. STEEP stands for "Sources, Transport, Exposure & Effects of PFASs."

More testing would need to be conducted to definitively prove the PFOS in the drinking water came from the Air Force base, Becanova said. But it is a likely suspect, she said.

“Since this facility is so close, I would think it is the most probable source,” she said. “Concentrations like this are usually associated with some big source of the chemicals.”

In the short term, small amounts of the chemical are not life-threatening to people. The greatest concern with PFOS and similar compounds is long-term exposure, which is why EPA set the advised health limit for the chemical in 2016.

The medical science surrounding PFOS is not completely settled. But researchers continue to study it for potential links to high cholesterol, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, development issues, immunological problems, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and kidney and testicular cancers.

Air Force firefighters spray foam on an engine and the fuselage of an Air Force C5 Galaxy cargo plane that crashed just short of a runway at Dover Air Force Base on Monday, April 3, 2006, in Dover, Del. The plane was carrying 17 people. File/Chris Gardner/AP

The compound can build up in people’s blood over time and is extremely difficult to clean up once it is released into the environment. That’s why environmental advocates are pushing for stricter regulations on the entire family of PFAS chemicals.

"What we really need is to require government testing and monitoring for these chemicals," said Jenna Reed, a policy analyst for the Union for Concerned Scientists. "Communities need assurances that their water is clean."

The lab results could add to the mountain of liability currently facing the U.S. Department of Defense. The DOD continues to find PFOS and similar chemicals at bases across the country, including three other military installations in South Carolina.

The Post and Courier shared its test results with the Air Force and the S.C. Department of Health and Environmental Control on Dec. 30.

Mark Kinkade, an Air Force spokesman, said the military would take The Post and Courier's lab results into consideration. But it would need to conduct its own testing at federally approved laboratories before it decides whether to replace the drinking water at Crescent, he said.

That testing, he said, could happen at some point over the next year.

DHEC, however, is moving quicker than that. The newspaper's finding prompted the health department to begin planning for its own water testing at Crescent within the next month.

That's something the agency specifically declined to do on its own last year.

"The health of our communities remains the top priority for DHEC, and we appreciate your assistance in bringing these test results to our attention," said Laura Renwick, DHEC's spokeswoman.

The lab results from the state will be shared with the Air Force, Renwick said. And if PFOS is detected, state officials will decide what needs to be done to protect the health of the community.

'A proactive, measured approach'

The Air Force already tested the six drinking water wells on Shaw Air Force Base, which more than 4,000 airmen and their families rely on for drinking water.

All of those samples came back clean.

But the military has been slower in checking the water systems that supply low-income and minority communities near the base.

Last year, the Air Force said its focus was on conducting additional groundwater testing at the air base first. Then it would consider sampling the tap water for nearby homes, following federal procedures.

"The Air Force is taking a proactive, measured approach to sampling off-base wells," Air Force officials said at the time.

“The Air Force’s priority is protecting human health and drinking water sources,” they added.

The Air Force’s environmental study from last year shows dozens of public and private wells are within a 4-mile radius of Shaw.

The Post and Courier chose to test the drinking water at Crescent because it was specifically mentioned in the study. The trailer park's water wells are within a mile of three of the contaminated areas under the 3,569-acre air base.

The newspaper also paid to sample the water used at the Ideal Trailer Park. That trailer park is less than a quarter-mile from another contaminated site near Shaw’s water treatment plant, but the lab results did not show any signs of chemical contamination in the drinking water there.

Christopher Higgins, an environmental engineering professor with the Colorado School of Mines, was not surprised by the newspaper's findings.

He's studied the movement of PFOS and other chemicals in groundwater. He said even a small amount of the firefighting foam, which is now being phased out by the military, can lead to significant chemical contamination in soil and groundwater.

"This is a national-scale issue for sure," Higgins said.

Grant Head just wants to know why there has been so little communication from the Air Force about the chemicals it found under Shaw and the potential threat it posed to his drinking water.

Head has lived at Crescent for more than four years, and regularly drinks the tap water at the trailer park. He doesn't understand why the Air Force is taking so long to pay for its own sampling in nearby communities.

"If there are questions raised, why wouldn't the water be tested?" Head said.

Grant Head, a Navy veteran, cuts wood at his residence at Crescent Motor Home Park on Monday, July 1, 2019, in Sumter County. Head has lived next to Shaw Air Force Base for four years. Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

The Air Force has promised on multiple occasions to replace drinking water sources, if significant contamination is found and the pollutants can be traced back to Shaw.

That could involve the Air Force paying for an advanced filtration system to remove the chemicals from the drinking water wells. Or it could require the military to hook up communities to another public water source.

Neither of those options have been implemented yet.

A regulatory breakdown

DHEC was also slow to respond to the groundwater contamination that was found under Shaw last year.

The state agency initially argued the contaminated groundwater under Shaw didn't flow off the base exactly in the direction of Crescent and its water wells.

And state health officials refused for months to sample the tap water at any of the neighboring communities around the Air Force base. They blamed the inaction on the federal government.

The EPA has recommended limits for PFOS in drinking water. But federal officials have yet to actually set an enforceable limit for the compound.

PFOS is considered an "emerging contaminant" by the EPA. It's one of thousands of industrial chemicals that are used in the United States but not routinely tested for in drinking water.

But that hasn't stopped other states from responding to PFOS and other PFAS chemicals.

Health departments in Michigan, New York and Minnesota, for instance, started wide-ranging programs to monitor for the chemicals in recent years. They investigated where the compounds were used in the past. And they started sampling water systems, large and small.

A growing number of states also established their own standards for PFOS in drinking water, and set those limits even lower than the EPA’s recommended 70 parts per trillion.

Wendy Brawley, D-Hopkins, wants South Carolina to join that trend.

"DHEC is our first line of defense to protect the people of South Carolina. We have to have a stopgap here to make sure we are looking out for the people in this state," said Brawley, who represents communities around Shaw. "I think DHEC needs to step up its regulatory and investigative authority."

"This is America. We should be doing a lot better than this," she said. "We should not be allowing any entity, private or governmental, to be contaminating our environment."

Brawley is concerned similar drinking water contamination might be found near other military bases in South Carolina. That's why she and several other state Democratic lawmakers sponsored a bill that would require DHEC to set a new limit for PFOS in South Carolina.

That bill could be taken up by the South Carolina Legislature as early as this month, when state lawmakers reconvene in Columbia.

"water" - Google News

January 05, 2020 at 03:32AM

https://ift.tt/36pxQpf

We found a chemical in tap water near an air base after SC failed to test for pollutants - Charleston Post Courier

"water" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2XpCTT3

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "We found a chemical in tap water near an air base after SC failed to test for pollutants - Charleston Post Courier"

Post a Comment